From 1000 Years For Revenge: International Terrorism and the FBI: The Untold Story in memory of FDNY Fire Marshal Ronnie Bucca, one of the fallen heroes of September 11th, who, like Paul Revere, tried to warn the intelligence community of the coming attack.

CHAPTER ONE

BLACK TUESDAY

On the morning of September 11, 2001, the greatest would-be mass murderer since Adolf Hitler was locked down in solitary confinement in a Colorado prison. In a seven-by-twelve-foot cell at the Supermax, the most secure of all federal jails, Ramzi Yousef sat waiting like a bird of prey. Small, gaunt and reed-thin, with close-cropped hair and two milky gray eyes, he looked across his cell at the stainless steel toilet and sink, below a shelf supporting a thirteen-inch TV. It was Yousef’s only link to the outside world. As CNN played silently in the background, his eyes darted across the dog-eared pages of his Koran.

Yousef may not have known the precise moment of the attacks, but he was sure they would come. After all, he’d set them in motion six years before in Manila. The idea of hijacking jetliners laden with fuel, and using them as missiles to take down great buildings, had come to the bomb maker after he’d tried to kill a quarter of a million people with his first Twin Towers device in 1993. He’d gone on to plot the deaths of President Clinton, Pope John Paul II, and the prime minister of Pakistan, while hatching a fiendish plan to destroy up to a dozen jumbo jets as they flew over American cities. But his most audacious plot involved a return to New York to finish the job he’d started in the fall of 1992. In one horrific morning, suicide bombers trained as pilots would take the cockpits aboard a series of commercial airliners and drive them into the Trade Center towers, the Pentagon, and a series of other U.S. buildings.

Now, just before 6:45 a.m. Mountain Time, as Ramzi Yousef sat in the Supermax reading the Koran, he heard muffled noises on the cell block: inmates shouting. One of the prisoners down the corridor had been watching CNN and now he was screaming. A guard rushed to his cell, went inside and saw the devastation.

He yelled, “Some plane just hit the Trade Center.”

Yousef quickly looked up at the black-and-white TV above his head. His eyes wide at the site of the North Tower burning, he turned up the sound and heard the voice of an eyewitness: “I just saw the entire top part of the World Trade Center explode.”

Yousef rocked back, amazed himself at the execution of his plan. He stared at the news footage of racing FDNY engines, terrified evacuees, and bodies dropping from the towers. Then, from the Battery, a camera captured UA Flight #175 slamming into the South Tower.

Another onlooker described it as “a sickening sight.” But Yousef, the master terrorist, saw it as the culmination of a dream and the end to some unfinished business. He dropped to the floor, bent over, and gave thanks. “Praise Allah the merciful and the just, the lord of the worlds. We thank you for delivering this message to the apostates.”

Later that morning, his cell door swung open and a pair of FBI agents from the Colorado Springs office came in. They stood in the three-foot-wide anteroom between the solid steel cell door and the bars to Yousef’s cell.

The convicted terrorist got up from his bed and approached the bars as the two agents presented Bureau IDs and identified themselves.

“Why do you come here?” he demanded.

One of the agents nodded to the TV behind Yousef, still tuned to CNN.

“Did you have anything to do with that?”

Yousef shot back: “How would I possibly know what was going on from in here? Besides, I am represented by counsel. You have no right to question me without my attorney present.”

The two agents eyed each other. Now they were facing Yousef the lawyer, the man who had represented himself throughout the entire three months of the Manila airline bombing trial.

“I have nothing else to say to you,” snapped Yousef. He turned up the sound on the TV and sat back down on his bed.

The agents withdrew, but within minutes the steel door swung back open and two Bureau of Prisons guards stormed in.

As one began to unlock Yousef’s cell bars, the other one shouted, “Get up and face the wall.” Yousef stared at him defiantly for a moment, but then the guard slammed a black box and a belly belt chain against the bars, so Yousef got up. Now, as he faced the wall, one guard came in and quickly put the belt around his waist. The other one bent down and snapped on ankle irons and a chain.

“What is this?” shouted Yousef. “What are you doing?”

“Changing cells,” said one of the guards. He turned off the TV. “Hands clasped in front of you.” Yousef ground his teeth, but complied, as the guard snapped the black box onto his wrist—a six-inch long solid restraint that rendered the prisoner’s hands completely immobile. The guard locked the box onto the belly belt, making it impossible now for Yousef to strike out with his arms or fists. The guards turned him around and shuffled him out of the cell, moving him down the corridor of “D” wing, past the cell of the infamous Unabomber, Ted Kaczynski. (For a time, this so-called “bombers row” had also housed convicted Oklahoma City bombers Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols.)

One of the guards unlocked the door to an empty cell and moved Yousef inside as he continued to rant.

“Why are you moving me? My papers—you have to let me take my Koran!”

But when the guards had him locked behind the cell bars, they slammed closed the steel door and went back to Yousef’s cell. There they began to toss it, searching around the mattress and on the shelf beside the bed, throwing Yousef’s letters, papers, and drawings into a plastic garbage bag. The units on the maximum-security “D” wing are supposed to be soundproof, but as the guards worked to clean out Yousef’s cell, they could still hear him screaming down the corridor.

“Why are you doing this? Why would you think that I could have any knowledge of this thing that happened? I’ve been in this place locked down for years. Do you hear me?”

In fact, Yousef’s knowledge of the plot was quite precise. He had designed it with his uncle and his best friend back in 1994. It had now been executed almost exactly as he intended. Only the details of the timing had been unknown to him.

Another thing Yousef couldn’t possibly know was that across the country, earlier that morning, a woman who’d almost stopped him had watched the devastation first hand. She had put all of this behind her years ago, or so she thought. But now the terror she’d been so close to preventing, was back. For FBI Special Agent Nancy Floyd, an old wound had just been ripped open.

THE VIEW FROM THE BRIDGE

She had come within weeks of breaking Yousef’s bomb cell in the fall of 1992, but her investigation had been shut down by a Bureau superior in New York. Now, just before 9:00 a.m., as she drove west across the George Washington Bridge on her way to an off-site surveillance assignment, Agent Floyd heard a report on her car radio about an explosion at the Trade Center.

She hit the brakes. Dozens of cars in front of her skidded to a stop, and traffic on both sides of the bridge ground to a halt as the morning commuters heard the news. Nancy shoved her gun into a holster on her belt, threw a jacket, on and got out of the car. She quickly crossed the center median and moved with dozens of other onlookers to the south side of the bridge.

Down the Hudson River, at the tip of Lower Manhattan, smoke billowed up from the North Tower. Nancy listened to a radio broadcast from a nearby car. It was still early in the attack, and the onlookers around her were speculating: “Are they sure it’s a plane?” “Maybe a gas leak?”

Standing there on the bridge, though, the forty-one-year-old special agent from Texas knew in her gut what it was: an attack by Middle Eastern terrorists—and not just any attack, but one hatched in the brilliant but deadly mind of Ramzi Yousef.

Minutes later, UA Flight #175 roared down the river a few thousand feet above them. For a moment it looked as if the 767 was pointed toward the Statue of Liberty in New York Harbor; then it turned to the left, and slammed into the upper floors of the South Tower.

Back in 1992, through Emad Salem, an Egyptian informant she’d recruited, Nancy Floyd had come so close to the men around Yousef that she could almost smell them. By then, Ramzi Yousef was hard at work at an apartment in Jersey City, building the 1,500-pound urea-nitrate-fuel oil device he would soon plant on the B-2 level beneath the two towers.

Now Nancy watched those towers as they burned, knowing that though he’d been in federal lockup since 1995, this was somehow the fulfillment of Yousef’s plan. For Agent Floyd it was a vindication, but she took little comfort in the thought.

Her attempt to expose the first Trade Center plot had almost cost her career. Only now, years later, had she begun to recover. She’d put in for a transfer to a small FBI regional office in the far West; her request was granted, and now Nancy was only eighteen days away from leaving New York.

Long ago she’d tried to bury thoughts of Yousef and the 1993 bombing, but now she couldn’t stop thinking about him—especially after a call she’d received that past August from her old informant Salem. He’d been in the Federal Witness Protection Program ever since testifying against the cell around Yousef and Sheikh Abdel Rahman. Largely on Salem’s word, the blind Sheikh had been convicted of a plot to blow up a series of New York landmarks, including the tunnels leading into Manhattan and the very bridge Nancy Floyd was now standing on.

But years before, Floyd had been prohibited by the Bureau from taking Salem’s calls, or ever discussing the details of the original bombing with him. In all the years since, even when Salem had been diagnosed with cancer in 1998, Nancy had never broken the silence.

Then, a few weeks before 9/11, Nancy was working an FBI undercover assignment when Salem sent word that he wanted to talk to her.

They never connected. So she never heard what he wanted to say.

Now, as she stood watching the towers burn, Nancy Floyd felt a cold throb at the base of her spine. Could Emad have been calling to warn me about this?, she wondered. She would never know. Only in the summer of 2002, months after the attacks, did Nancy Floyd become aware that another investigator had been on a parallel course.

Along with the word “tragedy,” September 11 was the day the word “hero” took on new meaning. For the FDNY, the statistics were numbing: 343 members of service lost their lives. Ninety firefighters in the Department’s Special Operations Command were wiped out. Rescue One, the preeminent heavy rescue company in the world, lost eleven men in a house of twenty-five. 9/11 was a day full of terrible ironies, but one of the cruelest involved a man who was already a bona fide legend in the FDNY, fifteen years before he ever roared down to Liberty Street and raced up the stairs of the South Tower.

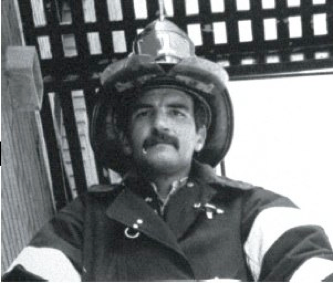

Ronnie Bucca was a forty-seven-year-old fire marshal with the FDNY’s Bureau of Fire Investigation. A veteran firefighter himself, Bucca had investigated the original WTC bombing in 1993—and had come away convinced that the perpetrators would return to finish the job.

Over the next six years, as he educated himself on Islamic fundamentalism, Bucca found himself continually frustrated by the FBI’s inability to appreciate the bin Laden threat or share the intel. Despite the fact that he had a Top Secret security clearance as a Warrant Officer in a high level Army Reserve intelligence unit, Bucca was repeatedly frozen out by members of the NYPD-FBI Joint Terrorist Task Force, one of the key Bureau units hunting Yousef. His frustration reached a fever pitch in 1999, after he uncovered startling evidence that a mole with direct ties to the blind Sheikh was actually working inside FDNY headquarters. Now, astonishingly, on that morning, as Nancy Floyd watched from the George Washington Bridge, Ronnie Bucca was on the 78 floor of the South Tower with a hose in his hand, trying to beat back the flames.

THE FLYING FIREFIGHTER

Just after noon on September 16, 1986, Ronnie Bucca was working as an outside vent man on the day tour at Rescue One, the busiest heavy rescue company in New York City. Ronnie, his lieutenant, and four other firefighters had just knocked down an electrical fire in the West 20s and were “taking up,” heading back to the house on West 43rd Street, when they got the call from Dispatch. A 10-75, the FDNY code calling for backup assistance from a rescue company, had been transmitted for Box 22-1138 at 483 Amsterdam Avenue on the Upper West Side. 40 Engine and 35 Truck had responded. Dispatch indicated that the “fire ground” was on the fourth floor, moving toward “exposure two,” the right side of the building.

In the cab of the company’s big Mack R truck, Lt. Steve Casani, a blue-eyed Irish-Italian bear, turned to his driver (known as the chauffeur) and said, “Hit it.”

The siren roared and the enormous “toolbox on wheels” headed up Eighth Avenue to the Upper West Side. Heavy rescue companies like “One” were created to provide backup for working fire suppression units. Their job was to get inside, help move the hose, help vent the flames, and look for bodies, both civilians and Members of Service (other firefighters).

“By the time we got there,” recalled Casani, “The fourth floor was engulfed. 40 Engine needed help, so we went to work.”

Hydrants were tapped, hose lines were pulled, and 35 Truck’s ladder rose toward the roof of the five-story old-law tenement. As the men from Rescue One jumped off the truck, they quickly pulled their Scott Air Packs over their Nomex turnout coats.

Ronnie Bucca, a darkly handsome ex-Green Beret Reservist who’d made dozens of jumps with the 101st Airborne, was known for his attention to the gear. He took an extra second to buckle his harness so that the thirty-five-pound compressed air bottle on his back would stay secure.

It was a move that would soon save his life.

Ronnie grabbed a Haligan forcible entry tool and took off with firefighter Tommy Reichel into 485 Amsterdam, the tenement next to the fire building. A five-mile-a-day runner, Bucca took the steps two at a time. At 5’9” and 165 pounds Bucca was slightly built compared to some of the “beefalos” in the house, but what he lacked in size he made up for in tenacity and heart.

At the roof, Ronnie burst through the door and was immediately pushed back by the heat. Even under his mask he felt it. Next door, the fourth floor at 483 Amsterdam was an inferno. Just then, over the Handie-Talkie radio clipped to his turnout coat, he heard a Mayday from Lt. Dave Fenton from 35 Truck, who was trapped on the 5th floor. There was a fire escape outside, but in a classic New York irony, the windows were covered by security “scissor gates.” Designed to keep predators out, the gates had locked the lieutenant in, and he was running out of time.

Ronnie climbed through a gooseneck ladder onto the fire escape. As soon as he hit the rusted metal he slipped. The broken glass on the grid was like ice. Worse, smoke thick as pea soup was coming out of the windows behind the gates. Ronnie tightened his mask and switched on the Scott’s bottle. Compressed air filled his lungs. He moved cautiously to the edge of the fire escape and leaned over to smash the glass.

The smoke rushed out. Ronnie leaned over again and made a stab with the Haligan tool, trying to hook the gates and pop them free. But as he swung out, he slipped on the glass and went over the edge, going down past the fourth floor, then the third, falling face up as he dropped.

Miraculously, at the second floor level, the Scott’s Air Pack he’d so tightly cinched hit a metal conduit --a two-inch pipe across the alley that delivered electricity to the building. The force of the impact flipped Bucca 180 degrees and partially broke his fall.

He landed hard in a pile of debris on the ground level. The last thing he remembered was hearing a cracking sound.

At that moment, Lt. Fenton broke free. He moved to a fifth floor window, which he smashed to help vent and get air. But when he looked down, Fenton saw Ronnie’s body lying in the alley. His boots were twisted outward as if his legs had snapped. Bucca wasn’t moving.

“Jesus,” Fenton thought as he clicked on the Handie-Talkie.

“Mayday. Mayday. Man down in the alley.” He didn’t wait for a response. Fenton took off down the stairs.

Now, as he fought the blaze with firefighter Tom Reilly on the fourth floor, Lt. Steve Casani heard the distress call. The two of them rushed to the window and looked down.

“Christ,” said Casani. “I just lost my first guy.”

Fenton was first to hit the alley. When he saw Ronnie he was sure he was dead. But he leaned down, felt Bucca’s neck, and got a pulse. There was respiration, but maybe not for long. Fenton quickly pulled off his own turnout coat and covered Ronnie as Casani and Reilly burst into the alley from upstairs.

Right away, Casani jumped on the radio. “I need a Stokes basket and a bus,” he said, using FDNY speak for a rescue stretcher and an ambulance. Roosevelt Hospital was closest, but Casani demanded they head to Bellevue, which had a trauma unit. The only problem was, Bellevue was fifty blocks south and clear across town. Reilly didn’t think he heard right.

“Lieu, East 31st? At noon on a Tuesday? We’re on the fuckin’ West Side.”

“Then call the fuckin’ P.D.” growled Casani. “Have ‘em clear Fifth.” He looked down at Ronnie. “I am not gonna lose this kid.”

Minutes later the siren roared. Casani was in the back of an FDNY rescue unit gripping Ronnie’s hand as the ambulance cut through Central Park and did sixty behind Rescue One’s Mack R, cutting a swath through the noon traffic down Fifth Avenue. As the chauffeur looked left and right, virtually every intersection had been blocked off by an NYPD sector car, an FDNY ambulance, or a piece of fire apparatus. It was perhaps the greatest single midday hospital run in FDNY history, and soon the radio stations got word.

The anchor on WINS Radio said that traffic was being blocked on Fifth Avenue between 96th and 34th streets. Mayor Koch and Cardinal O’Connor were on their way to Bellevue. A firefighter had been badly injured after a five-story fall; his name was being withheld pending notification of next of kin.

Ronnie’s brother Robert, a former medic with the 82nd Airborne who was then a cadet at the Police Academy, got the first call. He asked the FDNY to patch him through to Ronnie’s wife, Eve, who was in the kitchen of their modest home north of the city. Eve’s father, Bart Mitchell, had been an FDNY Battalion Chief with the 12th in Harlem. Her grandfather was a retired FDNY lieutenant who’d worked the Bronx. Growing up, she’d heard the phone ring dozens of times before, but never for something like this. Robert told her not to worry. He’d pick her up in an NYPD sector car for the trip downtown.

When they roared up to Bellevue with siren and lights flashing, there was a small crowd of reporters outside keeping the deathwatch. Ronnie’s older brother Alfred, who worked for the Transit Authority, was outside along with Ronnie’s parents, Joe and Astrid, and a few of his buddies from the 11th Special Forces. Together they moved past the press gauntlet.

In the hallway outside ICU, Eve could feel her heart pounding until the door opened and Lt. Casani walked out, still in his bunker coat. She hesitated, studying his face. Then he grinned. “It’s gonna be all right.” He opened his coat and hugged her.

“At that moment I knew we had a miracle,” said Eve, thinking back. She moved quickly inside toward Ronnie’s bedside and saw that though he was lying flat, barely moving, he was conscious. She bent down and kissed him. Ronnie lifted a finger and Eve squeezed it. He motioned for her to come close and whispered, “Wasn’t my time, Hon.”

Eve bit down on her lower lip, holding back tears. Just then, a young female resident came up behind her. Dr. Lori Greenwald-Stein was holding a set of X-rays. She motioned Eve aside and put the X-rays up on a light box. Ronnie had sustained multiple contusions and lacerations. He’d broken his knee and the first lumbar vertebrae in his back. It was a compression fracture; otherwise Ronnie would have been paralyzed.

Eve closed her eyes.

“Lucky to be alive,” said the doctor. Then she leaned in and whispered, “But if he walks, it’ll probably be with a cane.”

Grateful as she was, Eve rocked back at the news. Her husband had been a firefighter for nine years, and was planning to go the distance. Her father had done thirty-five, and so had his father before him. “Ronnie was always first into the burning building,” said Eve, thinking back. “As a paratrooper he was the first one out of the plane. The idea that at the age of thirty-two he might spend the rest of his life as a cripple, didn’t even occur to him.”

Later, when some of the family members had left, Eve moved close to Ronnie’s bed. Eyeing the monitors measuring his vitals, she tried to cope by using her Irish. “Hmmm,” she said. “Pretty cheesy way to get out of the house painting.”

Ronnie tried to smile, but his face ached. He gestured her closer. Eve bent down next to him and he whispered, “I’m goin’ back.”

“You mean Rescue?”

Ronnie nodded. Eve was stunned. As well as she knew her husband—how he’d made it out of the Queens projects to qualify for the Green Berets; how he’d earned a position in an elite Screaming Eagles air assault unit; how he’d been cited for bravery by the FDNY—she couldn’t quite believe what she was hearing. Rescue One was the Special Forces of the FDNY. They went on seven to nine hundred runs a year. The idea of qualifying back into that house after suffering such trauma was unthinkable. Besides, after a life-threatening injury that was sure to leave him at least partially disabled, Ronnie could retire with a three-quarter tax-free pension. A thousand other men would have opted out. Now, looking down at him in the half-body cast, Eve was apprehensive.

“What about light duty?”

“No,” said Ronnie. “It’s Rescue.”

And a year later, almost to the day, Ronnie Bucca was rappelling down a wall at The Rock, the FDNY’s Fire Academy on Randall’s Island. After months of rehab—he began walking slowly, with a cane, then graduated to a treadmill and moved on to weight training—Ronnie Bucca had shed his body brace and completed the “rope course.” It was the last phase of re-training, allowing him to qualify back into Rescue One. He had finished each of the course evolutions: moving the hose, working the ladder, proving he could lower himself on a rope down the side of a building or lower an injured victim. Even the Mask Confinement Course, where he had to wear a Scott’s mask with its face plate blackened and get through a complicated maze with a limited amount of air in the bottle. This was the one phase of rescue training where most firefighters washed out. But Ronnie did it under the clock, with seconds to spare.

“It’s difficult to emphasize what an achievement this was for him,” said Paul Hashagen, a big 6’5” Rescue One chauffeur who had gone through Probie School with Ronnie. “You’ve got eleven thousand men in the department. A few hundred of the most competitive guys make it into Special Operations Command (SOC) which comprises the Squads and a Rescue company in each of the five boroughs. But everybody wants Manhattan, and there are only twenty-five spots in Rescue One. To re-qualify back into that house after a five-story drop where you broke your back— I’ve got to tell you, that’s astonishing.”

But Ronnie Bucca was half Sicilian and half Swedish on his mother's side. Eve always said he got his stubbornness from both of them.

Now, as he rappelled down to the bottom of the wall, a half dozen of his “brothers” surrounded him and let out a war whoop.

One of them pasted a joke shipping label on the back of his helmet. It said, "This side up," but the arrow was pointing down.

The men cheered and lifted him up on their shoulders. Ronnie Bucca, henceforth known throughout the FDNY as “the flying firefighter,” was back.

Months later, Ronnie raced into a burning “taxpayer,” a one-story corner building down on Avenue D in Alphabet City. It was a three-alarm response. Heavy flames licked out of the first floor windows of an abandoned paint store where squatters had come to live in the frigid cold. The old paint cans left in the store were giving off a lethal combination of volatiles, creating a toxic cloud so black that Bucca couldn’t see his hand in front of him. He clipped a Nomex search rope with a carabiner onto a metal door jamb so he could find his way out. He donned his mask and gave himself air from the Scott’s pack, feeling his way on his hands and knees. It was the Mask Confinement Course all over again, only this time he was crawling past thousand-degree flames. As he inched his way into the store, Ronnie heard a faint whimper. The sound of a little girl.

Feeling his way along some old shelves, he found a door to a back room. Ronnie reached up and tried the knob but it was locked, so he used a modified Haligan tool to pop it open. Searing heat came out as he crawled inside. He could hear the little girl moaning. Ronnie pushed forward and shined his light.

There, huddled inside an old storage cabinet, he saw her two little eyes. She couldn’t have been more than eight, the same age as his daughter Jessica. She was dressed in a urine-soaked oversized Knicks T-shirt. The little girl was half-dead. So Ronnie reached into the cabinet and grabbed her. She was gagging, coughing.

He took off the Scott’s mask and put it around her face, giving her air. The child’s respiration was starting to slow, so Ronnie quickly doubled back along the search rope until he could feel the chill from the outside air.

He was barely out the door when a woman screamed and rushed over. It was the girl’s grandmother. She threw her arms around Ronnie and hugged him for dear life as he passed the child into the hands of an EMS medic. Ronnie dropped down on the curb. The pain in his back was throbbing, but he’d refused to take any medication beyond aspirin; he didn’t want to let on to Lt. Casani or the other men how much the broken back still dogged him. He was about to get up and go back inside when the lieutenant came over and motioned for him to stay down. “They’re all out,” he said, and Ronnie nodded.

He unclipped the buckle on the strap of the Scott’s harness—the one that had saved his life. As he watched the old lady jump into the ambulance with the little girl who was alive because of him, Ronnie knew that all the retraining and the rehab had been worth it.

Later, half a world away in a terror camp near the Afghan-Pakistani border, a fierce young jihadi would begin

another kind of training. Ronnie Bucca had dedicated his life to putting fires out. Soon, it would be Ramzi

Ahmed Yousef’s mission to start them. COPYRIGHT 2003 By Peter Lance